by Joe “GG” Imburgia for the Winter 2025 issue

One summer day in 1971, Richard Castellano got out of his car to take a piss on an unnamed road in Jersey City, in view of the Statue of Liberty. Three gun shots rang out, and he walked back to the car where Johnny Martino was slumped over the steering wheel. “Leave the gun,” Castellano told the shooter in the backseat. Then he added an unscripted addition: “Take the cannoli.”

The man slumped at the wheel got up. Dozens of crew members surrounding the car applauded — they got the scene in a single take. Millions of people have subsequently seen and remembered this staged mob hit after The Godfather was released in 1972.

“Leaving the gun” gets so much emphasis in The Godfather that it’s become standard practice for mafia hits portrayed in films like Goodfellas and television shows like The Sopranos. I can see the attraction to a storyteller: When a character drops the gun — so confidently, so coldly — and walks away with the cannoli, we see them as a different breed. The gun is incidental to their identity, a mere throwaway tool. They are killers, just as much as they are breathers.

Looking at actual mafia shootings, though, of which there have been many throughout Jersey over the past 80 years, the practice was far more uneven.

Twenty years before The Godfather was filmed, and ten miles up the Hudson, Willie Moretti met four friends and coworkers at Joe’s Elbow Room (the current site of Villa Amalfi). Moretti was well-known for allegedly holding a gun to the head of bandleader Tommy Dorsey to convince him to release a young Frank Sinatra from his contract, a backstory referenced with Johnny Fontaine in The Godfather. But some months before meeting his friends at Joe’s, he had been one of the few gangsters to speak to Congress in the Kefauver hearings on organized crime. He didn’t give Congress much in terms of actionable intelligence, though his performance drew a lot of laughs (when asked if he was part of the mafia he responded, “What do you mean, like do I carry a membership card that says ‘Mafia’ on it?”) Nonetheless, his garrulous nature was not appreciated by his colleagues, who were also concerned that he was mentally declining due to syphilis.

After greeting each other, laughing and joking in Italian, the four friends shot Moretti multiple times in the face in the empty dining room. When the waitress ran out from the kitchen, the four men were gone and Moretti was dead. A photo of his body in a pool of blood on the floor of the diner is featured in the “gang violence” sequence of The Godfather, shortly after Michael shoots Solazzo and McCluskey at a Bronx restaurant (remembering at the last moment his instructions to leave the gun).

One thing is clear in the photo, and also evident from the New York Times report from the next day: The shooters did not leave their guns. Apparently, in 1951, a gun was just too valuable, even for high-rolling mafiosi, to throw away every time they had to whack somebody.

The other notable feature of the photo is the laughing detective, standing over Moretti’s body, which gives a sense of the urgency they felt for solving the case. The waitress, who initially said she could identify the shooters, changed her mind, according to the New York Times report, and “gave unsatisfactory descriptions.” The police formed theories on the killers, but never arrested anyone. The media, like the laughing detective, seemed to take the murder in stride. Multiple newspaper accounts took delight in pointing out that Moretti’s last bet on the horse races, based on papers in his possession, was for the horse Auditing to show (finish in the top three). Auditing finished fourth.

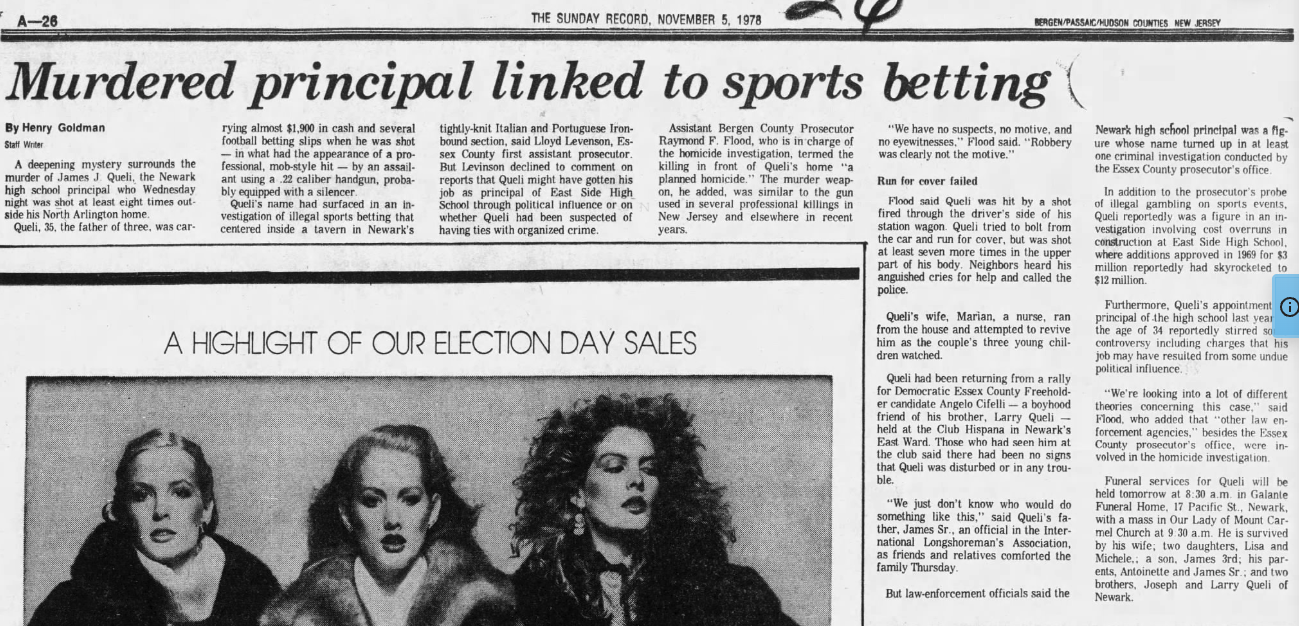

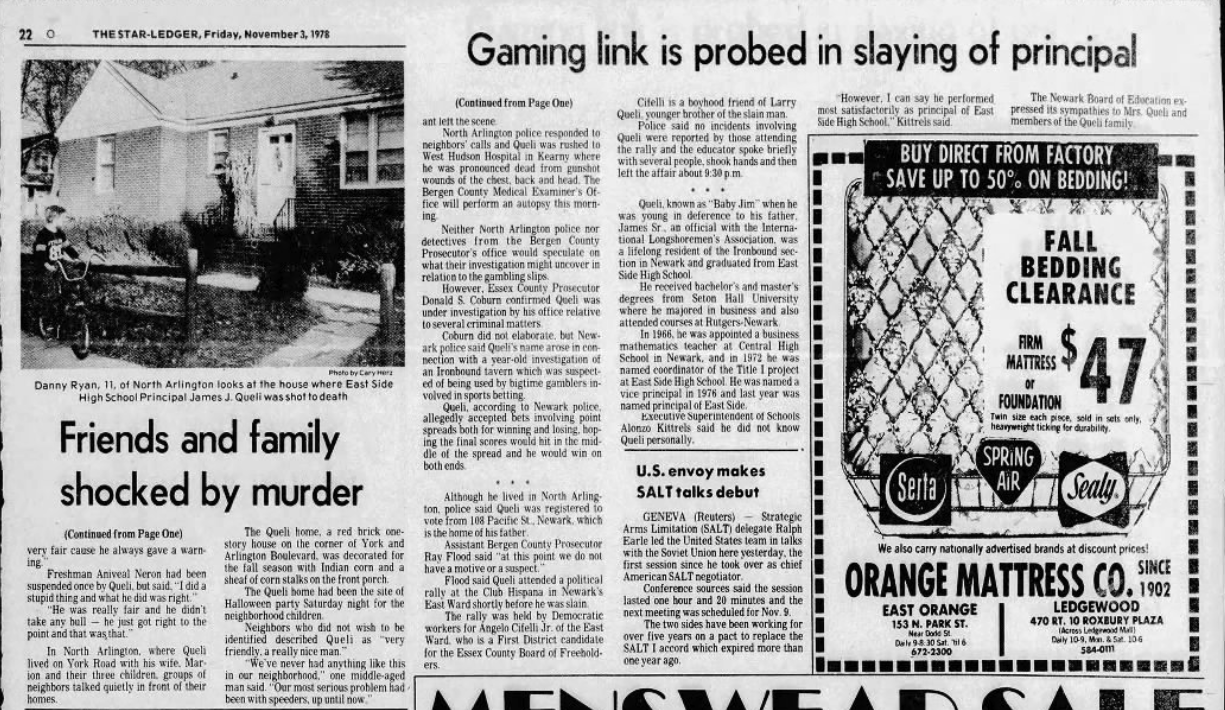

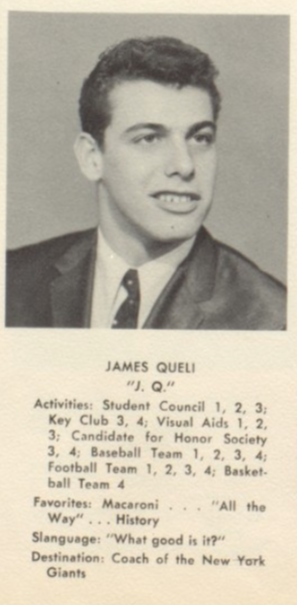

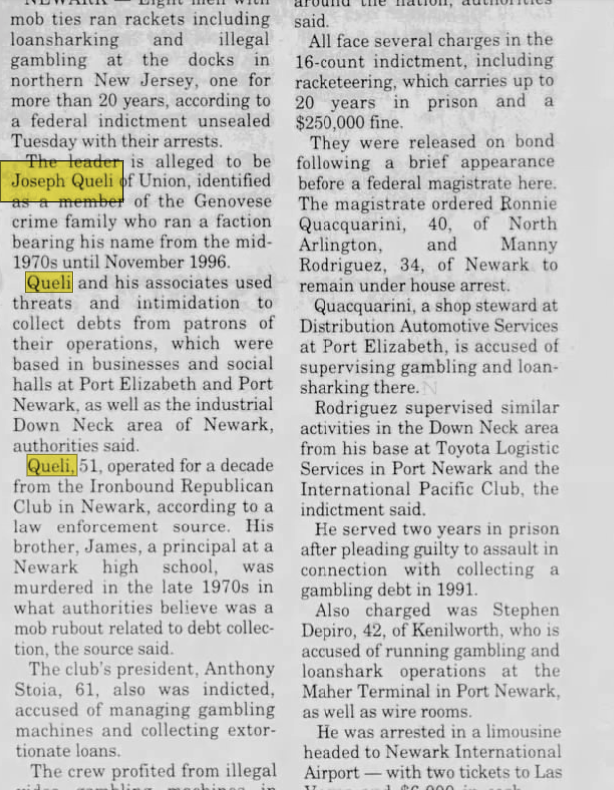

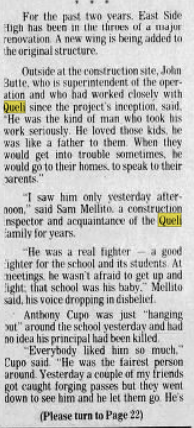

Twenty-seven years later, and six years after The Godfather came out, we do have an exception to the predominant pattern of keeping the gun. In North Arlington, New Jersey, about 10 miles west of the pretend Godfather murder, James Queli, Jr., was shot eight times outside his home in 1978. The 35-year-old principal of Newark’s East Side High School seems like an unlikely target for the mob, but there were suspicious betting slips in the pockets of the deceased.

The papers followed up on the murder for a few weeks, though it appears no one was ever charged. The gun, in this case, was abandoned. It was not coldly dropped at the scene, but chucked into a neighbor’s yard down the street. This gun abandonment may be an exception that proves the pattern of keeping the gun. Because the silenced .22 caliber gun that shot Queli was connected to no less than three previous murders, all of which were part of an epidemic of mafia hit jobs around the country using .22 caliber guns. Once considered too small for manly men, the mafia of the 1970s began to follow the lead of the CIA and use the .22 at close range. The small bullet, apparently, lacks power to exit the body, so instead a head shot bounces around inside the skull, delivering ample destruction to kill.

The .22 caliber gun that shot principal Queli was matched to the bullets found inside Vincent Capone (no relation to Al) in Hoboken two years earlier. Capone was a garbage contractor and mid-level gangster, primarily a loan shark, who was believed to have been killed by the Genovese crime family because of his cooperation with federal investigators.

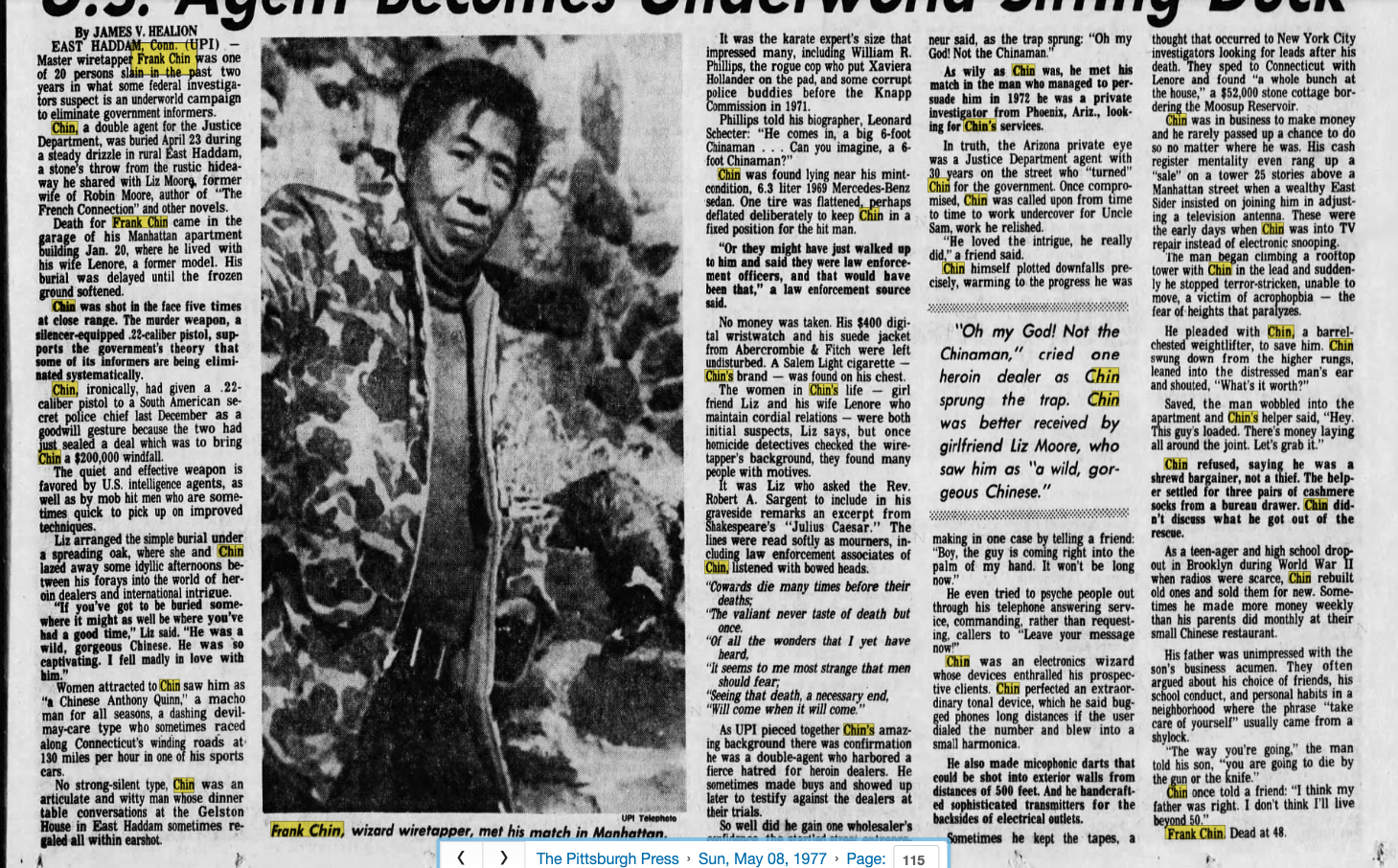

Frank Chin was also shot with this same gun in the garage of his Manhattan apartment in 1977. Chin had a fascinating story: The son of Chinese restaurant owners in Brooklyn, Chin dropped out of high school and rebuilt radios when they were scarce during World War II. He became known as an electronics wizard, and designed state-of-the-art listening devices, including specialized phone taps and microphone darts that could be shot into walls from 500 feet away. Chin was six feet tall, a barrel chested weight lifter, and was reportedly a charmer and the life of the party. He had a wife, who was an ex-model, and a girlfriend, the ex-wife of the author of The French Connection — but the wife and girlfriend apparently got along. He was described in the media of the 1970s as “a Chinese Anthony Quinn.”

He was allegedly a vigilante who hated heroin dealers, and set up his own sting operations to entrap them. But as an entrepreneur, Chin offered his wire-tapping services to whomever needed it — including both the feds and the mafia. While Chin had a lot going for him, he got into trouble because of his willingness to cooperate with investigators and testify at trials about his listening devices. Very likely, the zealous mafia prosecutors did not appreciate the danger they brought to him by securing his testimony. He was shot five times in the face. Richard “Bocci” DeSciscio, a Genevese family enforcer, was eventually convicted in his murder in 1989, along with multiple other crimes and hits.

But why was Queli, the young high school principal, shot a year later with the same gun? My instinct was to sympathize with this man — a public school professional who simply wracked up too many gambling debts. But gambling alone can’t explain it. After all, when does it ever make sense for criminals to kill a gambler? Breaking fingers and kneecaps, sure, but dead men only pay in blood, not in cash. Given that the same weapon was used on other individuals who were cooperating with investigators, my thought turned there next: Was there a mole at the FBI, tipping off the crime families to anyone who was sharing evidence? Were the investigators too embarrassed to reveal that their own clumsiness caused this relatively innocent principal to be gunned down in front of his house?

Maybe.

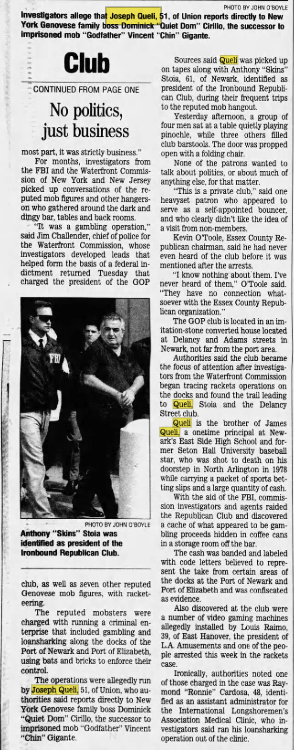

But it’s also possible Queli was more than just a gambler. A few weeks after his death, a cloud began to form in the media reports on the investigation of his murder. Beyond the betting slips in his pockets, there was talk of extensive connections to an illegal sports betting ring, and many wiretapped conversations between the principal’s office and an implicated bar in the Ironbound neighborhood. There were questions about why such a young and inexperienced educator should be appointed principal of a large high school. There was the situation of the ongoing renovations at East Side High, which had blown past its original $3 million budget and was now running at $12 million. An anonymous investigator told the Times, “We’re satisfied he was very heavily connected with organized crime.” A decade later, FBI documents evaluating evidence from many of these murders wrote, “He was … known to have ties with the Genovese family.”

Digging around a bit, I found a Facebook post from eight years ago, in which a former East Side High School student recollects the 1978 murder of his principal. The post garnered a fair amount of nostalgia and memories, with some students recalling Queli fondly, and others insisting that he should be allowed to rest in peace.

The poster, however, had little sympathy for his old principal: “Racist piece of shit got what he deserved. I tell that story all the time to let folks know that gangsters/thugs ran the damn high school I went to. I saw [Queli] beat a 17 [year old] Puerto Rican kid with a bat for throwing a snowball.”

Other former students also chimed in with stories of loan sharking and betting. One mentions there were always stacks of free Dr Pepper, as if they fell from the back of a truck, available in the cafeteria. Another claimed that seniors were given free cigarettes.

The poster also added, “His younger brother was the first person EVER to call me a F^%Kin N****r… I was 11… he had to be at least 17.”

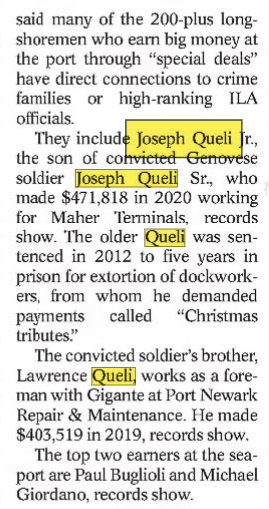

Another Queli brother was heavily involved in the docks. He pulled down an incredibly high salary with the International Longshoreman’s Association, and was repeatedly identified in the media as “a Genovese soldier.” In 2011 he pleaded guilty and was sentenced to five years in prison for making usurious loans (more than 50% interest!) to dock workers, in addition to demanding “Christmas tributes” from them. A more recent article in the New York Daily News pointed out that his son, Joseph Jr, was making half a million dollars per year at Maher Terminals in 2020. There is no doubt a deeper story behind all this, but it will take a harder-nosed crime reporter than myself to untangle it all.

I was just going for a neat “life imitates art” argument, hoping to say that real mafiosi began to leave their guns after the Godfather came out, heeding its advice. But that simply doesn’t align with the facts. Hitmen often keep their guns, and in the particular circumstances where it makes sense they will leave them, if they are cold-blooded enough.

But they always have, and likely always will, take the cannoli. 🏁

Selected source material/references:

content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0%2C33009%2C914890-2%2C00.html

nationalcrimesyndicate.com/9-restaurants-where-mobsters-were-whacked/

nomos-elibrary.de/en/document/view/detail/uuid/b6636bed-318b-303e-9053-74e7a2112245

nytimes.com/1951/10/05/archives/moretti-gambler-slain-by-4-gunmen-in-new-jersey-cafe-talkative.html

nytimes.com/1977/04/12/archives/fbi-calls-agents-to-parley-to-study-mysterious-killings.html

nytimes.com/1978/11/09/archives/slain-newark-principal-was-shot-with-gun-used-in-3-gang-murders.html

nytimes.com/1978/11/16/archives/slain-school-principal-is-said-to-have-had-criminal-links-bruno.html

onlyinyourstate.com/food/new-jersey/italian-eatery-mob-hangout-nj

reddit.com/r/Mafia/comments/vmcohk/the_body_of_guarino_willie_moretti_godfather_to/

time.com/archive/6852434/the-nation-death-of-a-wireman/

upi.com/Archives/1989/04/05/Witness-links-reputed-Genovese-enforcer-to-1977-killing/4873607752000/

Noisy Joy Z Opinions

Got good vibes to bounce back to the author? Gift them your gut reactions!

Leave a comment