by Dr. Francis J Dooley for the Winter 2025 issue

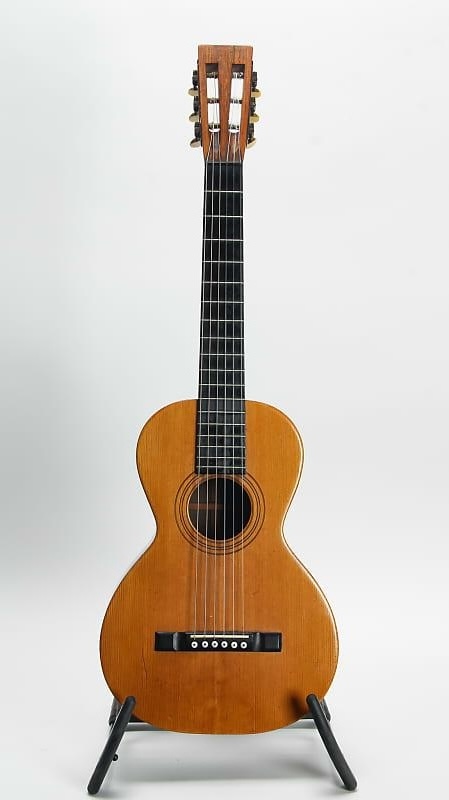

In the winter of 1887, the wind off Lake Michigan didn’t just howl, it bit. Inside the Lyon Healy factory on Wabash Avenue, the smell of warm hide glue and shaved Brazilian rosewood filled the air. A luthier, with hardened fingers from a lifetime of tension and wood, buffed the spruce top of the New Model Parlor guitar. Its body was small, light, and elegant; a “lady’s instrument,” the catalogs said. As he tapped the wood, the resonance was commanding and deep. He branded the internal center strip with the freshly struck Washburn Belt Logo, a permanent ink and fire stamp that would outlive him for centuries.

Its first owner was a young, well-educated clerk for the Pullman Palace Car Company. He christened the guitar Linnea, after the delicate twinflower of his Swedish homeland. For months, he carefully saved his earnings to buy her. In 1887, when a common laborer in the Chicago rail yards earned barely a dollar a day, a Washburn was a significant investment. While his peers chose $5.00 trade guitars from the Montgomery Ward catalog, he paid $22.00 for a professional grade “New Model.” To him, that price meant more than just wood and wire; it represented a way out of the dreary, soot-filled monotony of the railyards.

In the cramped boarding houses of Chicago’s South Side, entertainment was do-it-yourself. He felt at home with the guitar’s narrow waist fitting perfectly in his lap. While the city outside groaned with the industrial growth of the Gilded Age, he played Swedish folk melodies and popular tunes heard in Baker’s Theater. The notes rang out against the parlor’s wood paneling, a small, private beauty in a city of iron and coal.

Linnea didn’t stay in the parlor for long. By 1893, Chicago had transformed into a city of hope wrapped in white plaster and light. Tucked inside its wooden coffin case, the guitar journeyed to the World’s Expo. Under the shadow of George Ferris’s massive revolving wheel, Linnea was played for pennies as the world admired a million glowing electric bulbs. The guitar’s V-shaped neck smoothed under his thumb, absorbing the sweat of Chicago summers and the coal smoke of the city.

As every player passed, the guitar continued a long, rhythmic exodus. In 1917, it was strapped to a trunk heading for the Mississippi Delta, gifted to a nephew who replaced the gut strings with heavy steel. The increased tension bowed the bridge, adding a mournful, percussive snap to the sound. Linnea was gritty and persevered in shacks and on porches along the Yazoo River, with a spruce top defiantly bright, glowing with the rich, untarnished gold of what would become an heirloom.

A sophisticated turn in the late 1940s brought Linnea to a jazz pianist in Kansas City. Late-night songwriting sessions in smoke-filled clubs, the parlor guitar’s dry tone cut through the thick air of the breakneck harmonies. Linnea’s ladder-braced punch fascinated local jazz fans. She was treated with a mix of reverence and utility with careful repairs to the spruce top that kept her playable as the wood aged and settled.

By the 1960s, Linnea found her way into a dusty pawnshop in Greenwich Village. A young woman with flat ironed hair and a flower sewn dress pulled it from a stack of forgotten memories. She recognized the unmistakable soul of a handmade instrument that had been alive for nearly eighty years. To her, the fine cracks in the varnish weren’t damage; they were a map of the American century. She played it in Washington Square Park, its antique voice dancing with the smell of clove cigarettes and the buzzing energy of protest.

Decades passed in silence. On a cold morning, far from the Wabash factory and the Yazoo porches, Linnea found her way into my hands.

Now, she sits in a humidity-controlled room, a quiet reminder of fading craftsmanship. The ivory tuners have yellowed like old teeth, and the finish is etched with a thousand tiny scars from a century of stories. But when I pluck the strings, her sound is unchanged: a dry, woody resonance that echoes the escape of an 1887 winter, the ghosts of the World’s Fair, the smoke of jazz clubs and a changing world defined by protest. Sitting here, I realize Linnea is no longer just an instrument; she is a witness. I am her current guardian, but our time together is part of a larger song. As I play, she absorbs the air of 2025, preparing to share my story with the same honest voice she used to tell the tales of nearly a century and a half gone by. 🏁

Noisy Joy Z Opinions

Got good vibes to bounce back to the author? Gift them your gut reactions!

Leave a reply to therealgrantkoo Cancel reply